It’s a relief to be back, if even just through memory. Ripping the seal of a pink envelope is like cracking open the bookshop’s wooden door. The space has a distinct smell— my dad always said it was mildew, but to me it is a delicious blend of old books, their spines brittle and pages yellowed, and a pot of hazelnut coffee brewing in a corner. I spent hundreds of hours breathing in this air, and missing it is an acute form of homesickness.

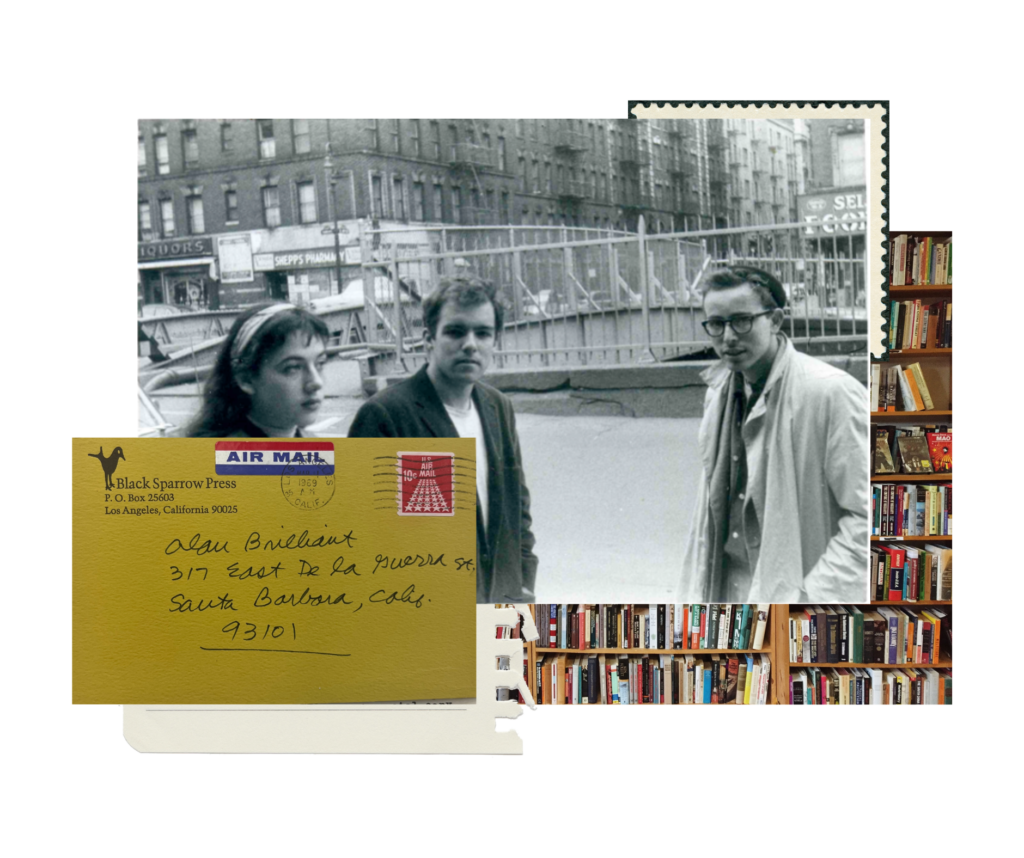

Glenwood Community Bookshop on 1212 Grove Street in Greensboro, NC, had thousands of books housed within, and I take immense pride in having touched almost every one. Early in 2018, I stumbled into a job with Alan Brilliant, then an 82-year-old man who had been involved in the literary community as a bookseller, poet and publisher for about 60 years, from New York to Santa Barbara. My father, his pastor, got me the job when Al told him about having too much work and I was preparing for a trip to Scotland that I could not pay for. I rooted myself in the shop’s ecosystem, sorting and shelving and organizing throughout three school years and warm summers, and a friendship between my family and Al bloomed. He’d come over for Christmases and attended my graduation, and my sister worked for him for several years, including after I left for college in 2021.

When I started working for him, Al was a figure on a pedestal, an example of the writer and person I wanted to be. By the time I was a junior, he was a close friend and mentor, sitting me down for hours at a time to talk. During my senior year of high school, I was one of the only people he saw due to the pandemic, and I took it upon myself to provide as much care as I could for him through grocery trips or doctors appointments. Al considered my creativity worthy of praise during a time that I did not, and his encouragement was foundational to developing my own self-worth as a creator.

When I went away to school as a freshman, Al began to write to me hourly, filling pages with descriptions of his days and questions about my own.

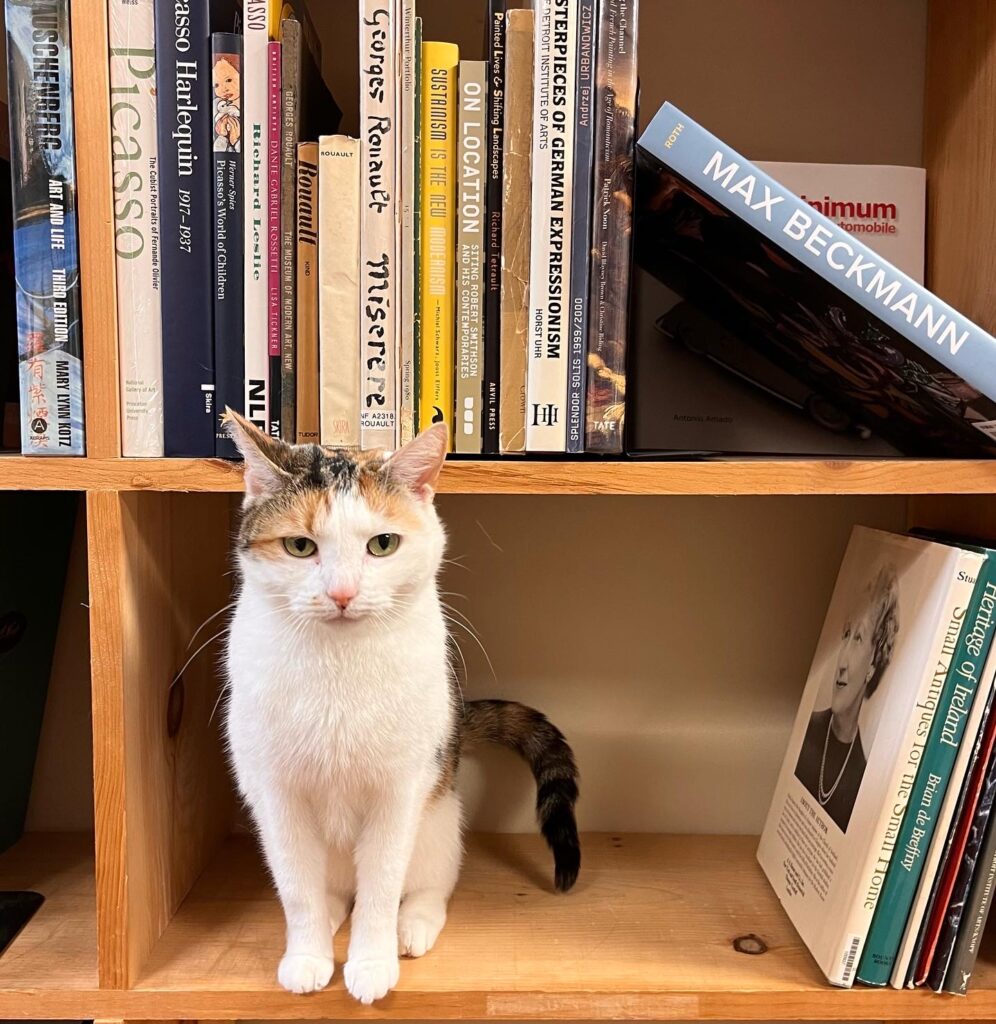

“Nuk says ‘Hello. Meow,’” he writes, and with his words Nuk, Al’s beautiful calico cat, greets me with a shrill yell, her meows bouncing along with her thin frame as she streaks to the front of the bookshop from a back shelf. She hates being held in your arms, but adores laps, and impatiently urges me to sit, so she can have full access to mine. After Al’s death in May of 2022, one of his friends took charge of Nuk, and I often wonder how she’s doing.

The envelopes are a splash of color in my desk drawer. Greens, purples, blues and yellows, stamped and carefully addressed:

SUSAN ELIZABETH BENBOW

114 COUNTRY CLUB ROAD, 311

CHAPEL HILL, NC

27514

Al’s handwriting on the envelope varies by day, and the pages of writing within vary in strength. Some letters were written in defiance of bouts of arthritis, letters shivering into piles of words that snowball into sentences. Others were written with such enthusiasm that the words blend together, as if he cannot express his ideas quickly enough. Some are calculated, neat, distinctly legible, when he is pensive and carefully plotting each stroke on blue, lined pages.

I have been living by the words of my late mentor and boss for the past few weeks, and know that Al lived by them for months, recording each moment and sharing each thought that crossed his mind. Each envelope holds between three and twelve pages of Al’s musings and observations, little dialogues he invented, information about interests he was researching. When they were sent, many ended up in a neat stack in my desk drawer, unread and unanswered. I was a college freshman, wrapped up in new friends and discoveries and a life that revolved around my college campus, though that’s no real excuse.

I still harbor a deep shame for how the envelope flaps remained firmly secured, a feeling that has crescendoed since Al died. I hid from these unopened letters, afraid that my negligence at some point took its toll or that there were clues within these pages about his eating habits, his declining health, his loneliness.

Irrational guilt and fear have sealed the envelopes for years, but I still saved each letter, carefully organizing them by date and tucking them into a yellow plastic box that Al gave me to start my own archive one day. Eventually, my curiosity outgrew my fear and I began carefully ripping at the seals.

“Beautiful day out,” he wrote on September 13. “I suppose almost all of your life these days is… indoors? Hello, Cameron!” —he wrote to my roommate and closest friend— “Hope you’re joyful. I expect you are!”

These letters, the key to Al’s life during a time where I was not able to be present, have traveled with me everywhere. I’ve read letters in cafes, on a porch swing in Hendersonville, at my family’s home in Greensboro, in my dorm room and outside, sprawled beneath oak trees or on wooden benches.

In some ways, I’ve invited Al into my life today as he invited me into his. We are in conversation in a way that I haven’t had since last May, and I am showing him pieces of my world, tucked into my backpack and tote bags and between the covers of my notebooks.

–

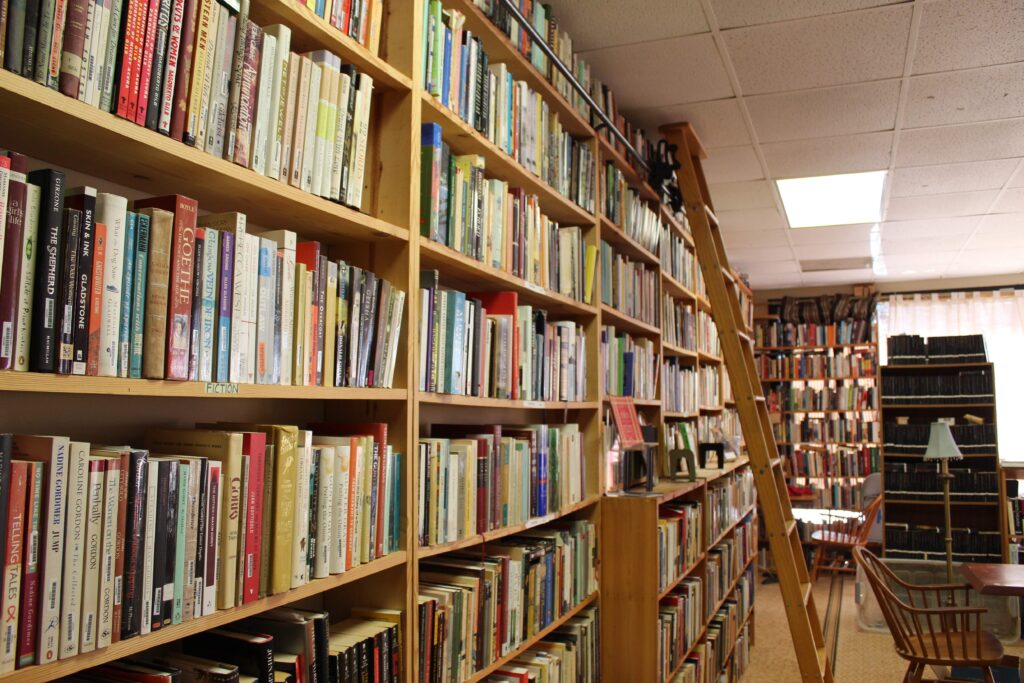

Every spare inch of Al’s strip mall unit on Grove Street has been covered in books. There are floor-to-ceiling shelves that line the walls, each of their shelves sagging with crammed-in volumes of history on one side, fiction on the other. The wall facing the street is taken up by a full window with metal bars, though shelves of novels block part of the window.

In the center of the shop is an open space full of dark, wooden tables and a futon Al bought for $400, which he slept on every night for as long as I knew him. I know that each day he narrates in his letters begins with him waking up on this futon, Nuk jumping from his chest as he sits up. She’d run to a spot in the bookshop where she could hide, or get sunlight. Often, the window provided both.

“Nuk’s in the barred S. window, observing the street. There’s been a faint sound of a dog barking the past 24 hours,” he wrote to me on November 1.

The bookshop doubles as Al’s home— it is where he eats, sleeps, entertains and works. For as long as I knew him, Al said it was where he wanted to die, and I occasionally feel a tinge of sadness that his wish went unmet.

Two rows of shelves create parallel aisles into the back of the space, one side follow the history section into art criticism and feminism, the other following fiction to a kitchen area with a mini-fridge, sink and the anthology and drama sections.

Sometimes he eats breakfast, though rarely before 11:00 a.m. and rarely with two other meals. His two most consistent forms of nutrients, orange juice and Boost protein shakes, often sit open on a side table for him to reach throughout the day.

Al’s weight would drop significantly during the last year of his life, something his friends would try to combat by bribing him with lunch visits or grocery shopping trips. The fridge frequently goes unused.

Al heads to the back of the bookshop, passing a nook of poetry books where a dark green chair sits, along with photos of poets Al published and loved, which I hung from the side of a shelf. At the back of the unit sits his work station, which is surrounded by books on art criticism and huge, colorful art books depicting collected works of individual artists or curated exhibits that I re-organized one summer.

The last section of the bookshop, philosophy and religion, is housed in a small room adjacent to the art books. This room also serves as a closet, and drawers in the corner are full of Al’s clothes, mostly hand-me-downs from friends. In the summer, he wears the same pair of khaki shorts and a t-shirt soft with age, changing into fleece-lined pants when the weather cools down. In high school, I would sometimes do laundry for him, which he would sheepishly offer up. It’s November, so he wears his jeans lined with fleece with a hole in the knee.

Al’s days are significantly emptier now that he has closed his Amazon storefront, where he would sell used and new books from the shelves to people across the country. At his work station, the counter where he would stand to carefully wrap books— first in bright tissue paper, then newspaper, then sealed within a manila package— sits empty, though it bears the scars of his meticulous craft and exacto knife.

He sits at his desktop instead, an ancient HP with a screen covered in downloaded files and programs. He answers emails, the only way he communicates with people, and opens Microsoft Publisher to access the autobiography he’s been working on for a week. He writes directly into the publishing software and prints as soon as he’s done.

“… I should tell you there might be competition for you in all these letters,” he wrote me on November 15. “I am thinking of writing one more book, as if 42 weren’t enough.”

It wasn’t until November 23, when the book was finished and his printer got jammed, that he wrote to me again, his print stoic and purposeful.

“Obviously, I’m trying to write letters again, as I completed my book, “Autobiography” and have a few clothbound copies done to give away,” he explained at the beginning of the letter. “Printer has serious blockage, a sheet stuck inside! So I can’t print anything right now.”

When the printer isn’t jammed, he patiently prints the 80-page book. He collates the pages in groups of eight, folding them in half with a bone folder, a weighted stick used to make crisp fold lines. He marks six places along the fold, an inch apart, to make holes with a pointed tool called a dowell, then threads a thick needle with waxed twine by some miracle, as bad as his eyes were and as much as his hands shook. He sews each group of eight with a thick needle threaded with waxed twine, then stitches them together.

The books are glued with a tool resembling a paintbrush with thicker bristles and paste from a bottle with a bright yellow label and set in a hand-cranked book press. The hardcovers are often made from supplies salvaged from previous projects— the copy Al gave me was bound in a swatch of green linen and covered with a case from a previous project.

Al’s publishing process has been simplified since he gave up his 50-year publishing company, Unicorn Press, in 2016, but he is still a devoted practitioner. He used to set type by hand in a printing press, and though he no longer has those resources, the holiness of book binding has followed him to Greensboro.

As he works, his age melts away and he is a snapshot of his younger self: a passionate writer, scholar, and publisher at 22.

–

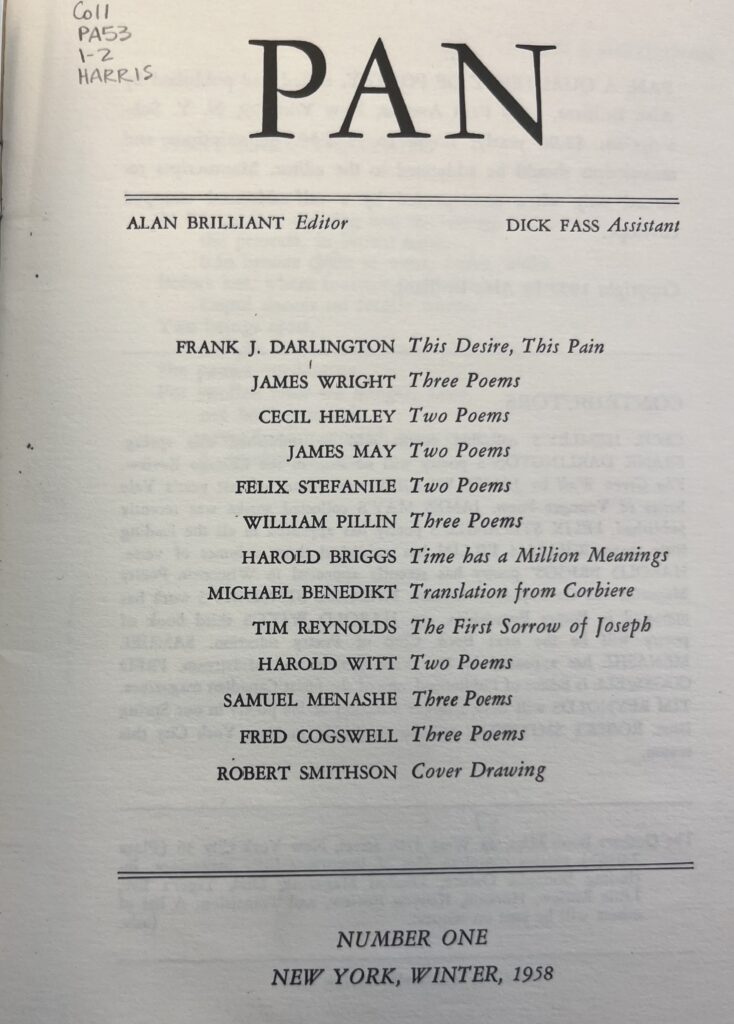

I stumbled across “Pan,” one of Al’s first books created at 22 years old, in his archives at Brown University’s library, barely a year after his death. Though the poetry magazine was made in 1958 during his time at Columbia University, it transported me to Grove Street, facing Al on his futon, a mug of coffee in hand. He would often sit my sister and I down for “staff meetings” to tell us stories of the authors he published and interactions he had, traveling from a college apartment in New York City to a middle-aged co-operative publishing house in Santa Barbara.

He was an eager literary scholar, landing a job at Frances Stelloff’s Gotham Book Mart as a young man. Gotham was an avant-garde literary hub, and Stelloff taught him about bookselling. It was here that he first brushed elbows with literary giants, and he’s told me that Georgia O’Keefe even had a studio in the space above the store.

The 1958 edition of “Pan” was sold in Gotham Book Mart, entirely produced by Al himself. The pages are stapled, not bound, and I wonder when he learned how to thread the needle and mark the crease with a dowel. I cannot imagine it being something he had to be taught— book binding feels so innate for Al, as if something he was born to do.

In 1966, Al began Unicorn Press in Santa Barbara, California. The press primarily published poetry, focusing on the convergence of art and the written word. Al published his own books, the writing of his wife, Teo Savory, and works by writers like Robert Bly, Tich Nat Hanh, and Federico García Lorca. Each was hand-set, often by Al himself, and printed in a limited run.

He commissioned the work of poets he admired and had deep roots in the literary community, focusing on writing that was political and anti-war. He himself resisted the Vietnam War draft and was arrested in peaceful demonstrations hundreds of times. The works of artful protest he published were printed on crafted paper, often accompanied by breathtaking, hand-carved stamped illustrations.

I like to imagine Al at 30 years old in Santa Barbara, pursuing and publishing what he believed to be the best poets of his generation. He stands over the printing press with ink-stained hands, laying the individual letters for a new poem. He sews books with deft, nimble fingers and chats with employees as the sun sets. His hands don’t shake, his eyes are sharp. He is the picture of health, his cheeks flushed from passionate conversation. He is everything the Al in front of me was, just set in a different frame, made of gold and radiating with a youthful glow.

–

“No, there’s nothing special about November 16th. What’s happened is that after several years too lazy or sick or old (I’m 85 ½) to write anything, I’m feeling particularly better and stronger,” Al wrote in the preface of his book, Autobiography.

Seven pages later, he recounts my favorite story of his– how Walt Whitman’s “Oh Captain, My Captain” changed his life in high school. It’s not a story I would have forgotten easily, but reading how he tells it is a gift. I can hear the cadence of his voice as he recounts how fascinated he was that Whitman had lived on the same street as him in Camden, New Jersey, and realizing that Whitman had printed and published his own books.

Autobiography at once tells the story of Al’s life in his words and in his materials, cobbling together past projects and passions to demonstrate who he is: a writer and a publisher who creates because he loves it. There is a notable glee in the letters Al wrote to me in the weeks surrounding this book, and he begins a second immediately, which is never published. Al’s hunger for learning is restored by creating this book, and reading this series of letters make me hopeful, somberly weighted down by hindsight.

I imagine his day continues, perhaps with a visitor bringing a reuben from Carolina Deli for lunch that he takes a few bites of. Maybe he takes a short walk up and down Grove Street. He bought a walker to help him get around better, and it would clatter up and down the broken sidewalk. In my mind, he stops to water his small garden— a little fig tree struggling to grow in a large pot, among others— and sits on a black metal bench I built for him, before he goes back inside. He is rooted in this quiet street in a poor neighborhood, and he is fed by its familiarity.

Al ends this November day with an usually large meal, eggs, sausage, Chinese cabbage, a salad and an English muffin, washed down with orange juice. It’s likely the largest meal he’s eaten in weeks.

“People who have listened patiently to all my stories have badgered me to write them down,” he wrote in the preface. “What they don’t add or say is, “You’ve going to die soon, and they will be lost.”

–

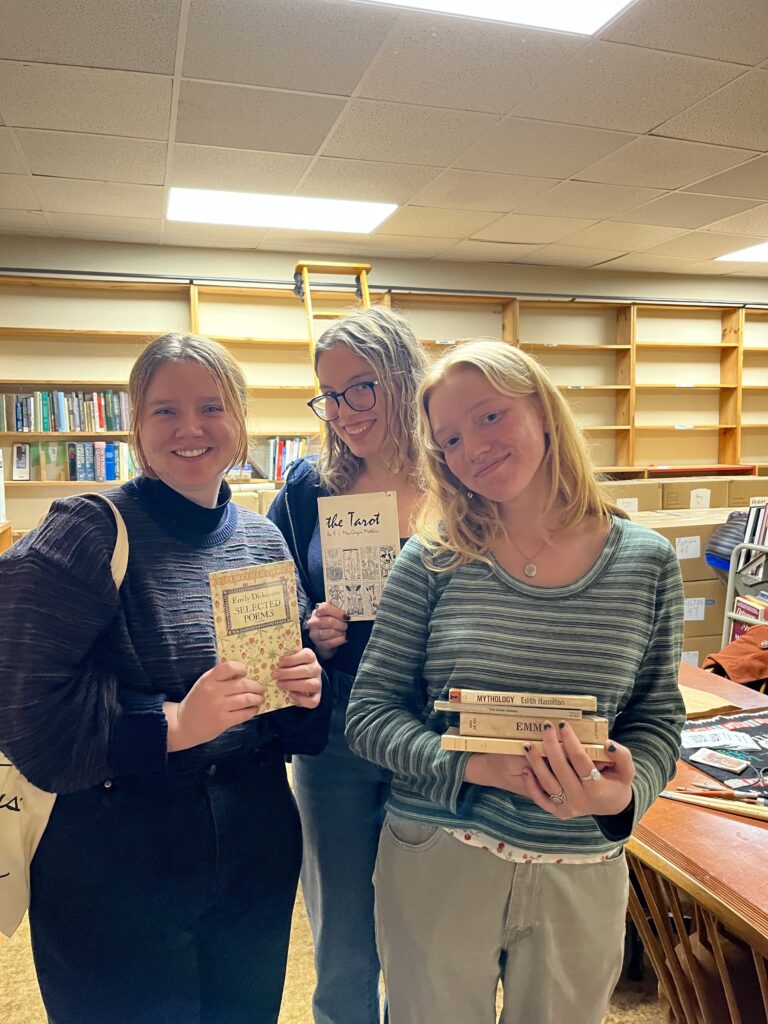

The last time I was inside 1212 Grove Street was the December after Al’s death, with a car full of my college friends. That night, friends of his gathered to say goodbye to the space and look through leftover books that Daniel and Lauren Goans, the inheritors of his will and his caretakers for the last months of his life, had selected for us. It was my final opportunity to introduce my friends to the space, and to Al by proxy.

I walked them through a bookshop with empty shelves and a yellowed carpet. I carefully pointed out each section, explained each way that I had reorganized it or interacted with it. I showed them how the shelves still bore labels — fiction, history, women and gender studies, philosophy, art criticism — that I had helped print and glue to the wood. That night, I still felt as if Al belonged in the space, as if he’d just stepped outside momentarily. I left with a wooden chess piece from one of his boards over the years, a glue brush, and a mass market copy of Jane Austen’s “Emma.”

–

Austen was often common ground for me and Al. He has admired her heroines and writing genius for decades, and I was in my formative years of experimenting with literature like Pride and Prejudice when I began working at the bookshop. We’d discuss her or Charlotte Brontë often when I worked, particularly focusing on my obsession with modern feminist interpretations of nineteenth century writers. Around the end of October in 2021, Al began re-reading all of Jane Austen’s novels, and his letters to me became annotated notes of his readings, summarizing plotlines and interjecting with his own thoughts.

“Although it is noways my first reading of “Persuasion,” I seem to be reading more slowly and more carefully than ever before,” he wrote on November 1.

As the carefully copied vocabulary words like “unfeudal” and “alloy” grew along with the descriptions of each copy he read, I can imagine the way Austen’s books slowly stacked up on his cluttered side table, down to the careful description of each copy he read.

Emma, a N.Y. Barnes & Noble Classics from 2004 with a bright red cover, with an introduction by Steven Marcus.

Mansfield Park, Al’s favorite, and likely the most damaged of the stack. I like to imagine it being a ratty paperback, though he never specified what copy it was.

Pride and Prejudice, my own introduction to literature. In my mind, Al read the Penguin Classic copy, published in 2002 with an introduction by Tony Tanner and lifted from the flimsy bookshelf at the front of the shop that displayed the several dozen Penguin Classic he’d collected over the years.

Persuasion, a clothbound Everyman’s Library book from 1992, which would have had a deep green cover with a black and gold band along the spine to boast the title.

We shared an affinity for the elegant binding of Everyman’s Library books, but I imagine that the spine was bent out of shape, crumbs indenting the crease between pages— Al didn’t always treat his books kindly, though he revered their contents more than anyone I knew.

I read Emma in the early days of the pandemic, mostly wanting an excuse to watch Anya Taylor Joy’s performance in Autumn De Wilde’s pastel-colored adaptation. I took comfort in how Emma Woodhouse stumbled through matchmaking and interacting with her peers, feeling as if her imperfections were an indication that my own could be redeemed.

Al, however, did not think of her as admirable, preferring Austin’s other heroines over this character I deemed to be complex and realistic.

“It is hard not to dislike Emma and her deceitful behaviour in [Chapter 7], as she forces Harriet to reject Mr. Martin’s love,” Al wrote on November 1. “Up to now, she has only acted foolishly. But in this slyness and deceit and untruth, she is really wicked.”

Al’s favorite of Austen’s novels, Mansfield Park, is my least favorite. I find Fanny, the heroine, to be dull and caricature-like, and I am particularly against her eventual pairing with her cousin. Al and I didn’t often disagree on matters stronger than fiction— I respected both his wisdom and judgment and he, for some reason, believed me to have similar qualities. We would butt heads over how quickly to finish projects or shop for groceries— I was a fan of dividing and conquering, but he liked to meander methodically down each Food Lion aisle. Ultimately, we were both people-pleasers, which meant that I was careful to provide him with choices rather than demands, and he accepted most of my suggestions with what I hoped was genuine support.

We did, though I never brought it up to him, disagree about what he called his “aloneness.”

When I feel out of control, I shut down. I spend a majority of my time trying to organize my own mind, which has fogged up, and it is too much to manage everything happening within me to bear dealing with anything outside. I rarely see people and I relish being by myself.

Being alone was a common theme in Al’s letters, and it was something he similarly seemed to crave.

There are moments in his letters where he tries to convince me that he is content with his aloneness, that he isn’t lonely— like when he wrote on September 28, 2021 that “Often, like now, I’d rather be alone. This is a new “old age” feeling….. Relief when someone says they’re NOT coming.”

I’m not sure if I believe him.

Not when he spent his entire days filling pages with his mundane moments, chapter-by-chapter analyses of Jane Austen novels or explanations of Guy Debord’s Situationist movements. I am skeptical of his joy in isolation when his letters become conversations, a call and response of ink and paper.

But I take things fast, while Al lingered. I wonder if there was something about aloneness that really was comforting and avoided loneliness, something that I have not slowed down enough to discover.

” “ALONENESS… It’s become essential to a joyful OLD AGE. Surprizing…..” he wrote on October 17.

In these letters, Al was at his best when he was enthralled by something— a writing project, a book series, a particular literary movement he was intrigued by. He was, like his name suggests, brilliant, and needed intellectual stimulation to be at his best, for himself and others. He would write pages-long descriptions about historic time periods he thought I should know about, political movements he was interested in (and sometimes, had participated in).

Eventually, Al got a subscription to an academic journal website, which only increased his hunger for knowledge and desire to share it. A bright yellow envelope postmarked for January 24 was stuffed with seven stapled pages of “Poetic Occupations: Artists as Narrator-Protagonists” by Jack Richardson from Ohio State University-Newark. The article details some examples of the merging of community, art, and activism that the Occupy Movement entailed. Al was a loyal member and leader in the Occupy Greensboro movement in 2011 and 2012.

“The meetings (up to 250 people) were held in the bookshop, then at 1310 Glenwood Avenue. There were dozens of protests and creative activities initiated in our back room!,” he wrote gleefully on January 20.

These are moments of clarity, passion and a glimmer of who I knew Al had been, written in hurried script, or calm, straight print that conveyed his enthrallment. It felt as if I was sitting with him, listening to stories of his political involvement and deep desire for change.

“It’s been nice being with you, Eliza, on a day when there was no one else,” he wrote on October 11.

I wonder if he wished someone was sitting there, listening to his explanations in person rather than through ink. I know he did have visitors— Charlie came to play chess, Will became a loyal friend later in life, Kathryn would take him shopping and bring him dinner and Alysse worked for him during the last few months of his time in the bookshop. But there were periods of time where Al saw no one, carefully-recorded instances in my letters, and I wonder if Al spoke at all on those days. I wonder how much he really ate without someone prompting him, and if loneliness ever crept through the wooden door, if it ever hovered above his futon.

I believe Al enjoyed being alone, perhaps more than I can understand. But I do not believe that there was never a time that he mourned the emptiness of his space— not when he had so many ideas to share.

“It’s twelve o’clock… let’s see if anyone shows up” he wrote on October 16. “But please don’t get the impression I’m ever lonely. I never am.”

That day, his last observation states that he had seven visitors, a note cheerfully provided and accentuated with an exclamation point.

–

A certain dread settles over me as I come to the end of my colorful stack of envelopes. I don’t know what I expected to find in them, but I don’t know if I’ve found it— something that would have warned me sooner about Al’s health, that I had not seen and could blame myself for missing. It’s hard to wrap my head around the possibility that these letters could just be soothing, a joyful experience of hearing Al’s voice again. The last letter I have from Al is a robin’s-egg blue and was mailed on February 18, 2022.

His health was declining, though his spirits seemed to remain high. Still, an undercurrent of unease settled between the lines of these last few letters as I read them– perhaps because I knew how the story ended.

There is another envelope in this archive, smaller than the others and unstamped. There is no address under Al’s name, written in my looping cursive. I didn’t know what address to use— by the time I had written it, Al was in Virginia, at a hospital or nursing home (I can’t remember where he was in early April, only that his health declined so steeply that he had spent several nights on the floor of the bookshop in early March, unable to get up after falling). I also think I was afraid to mail a response to words I hadn’t completely read.

This envelope is stuffed with two separate letters, addressed March 31 and April 14, and clippings of articles I’d recently had published in the paper. Inside, I sent well-wishes for his health, told him about a project I’m working on about Unicorn Press for an English class, and promised to visit when he is moved to a care facility in Greensboro. I was planning a trip to France at the time, and knew I wanted to see him before I left.

In one letter, I thanked him for the $500 he sent me for that trip— “You’re too kind to me, but it will be coveted & put to good use. Cameron and I are anxiously counting down the days!”

This is the only record of a check that I never cashed, aside from hazy memories of a letter written by someone who’d been helping him in the bookshop (his arthritis was too bad to be legible), the check tucked into a wallet. I’ve seemingly misplaced both pieces of this archive over the years, fading into memories and relying on recollection. I try not to think too much about this failed task, but it is hard to not admonish myself for losing a document so important that it is alive and vivid in my mind.

Their loss reflects the fears I have of my own dimming memory— I did not realize until Al died how much memory relies on physical reminders, and I’d neglected to see how few physical reminders I had in comparison to what I wanted to grasp onto.

–

Even the bookstore, once full of color in my mind and during my time off from school, has faded, packed in boxes and painted over with the white walls of what is now a thrift store. They are dotted with purple accents, a lovely touch that matches shelves displaying shoes and purses. The yellowing carpet has been replaced by light linoleum wood flooring, and racks of clothing have replaced the towering shelves of books. The landlords fixed the leaking ceiling tiles for the new tenants. Light pours into the space through the full wall of barred windows.

I found myself at 1212 Grove Street for the first time in a year on a bright October afternoon. I wandered slowly through the shop, brushing my fingertips along sweater sleeves and phantom shelves. The space has grown without the bookshelves lining the periphery and creating an aisle down the middle, but somehow it feels smaller, tighter, more constrained.

Perhaps that’s less the space and more my own body. I am overly aware of how tense I feel as I wander through the once-familiar space. My breaths are tight and my whole body feels stiff as I frantically quiz the bounds of my own memory.

“What shelf was here, and what books were on it?”

“What artwork hung from this wall? Was it a poem or a photograph?”

“The cabinet full of Marxist theory would have been here — right?”

The woman working today sits in the corner, scrolling on her phone, unaffected by what, to me, feels like a monumental loss. I am painfully aware that I have already lost details that I can’t even remember to quiz myself on, but also that she is painfully unaware that any of those details ever existed.

The thrift store is not devoid of Al’s touch. Perpendicular to the back wall is the same wrapping table we scarred with box cutters and made sticky with tape residue from wrapping Amazon orders. Tucked in the back corner is one of his wooden chairs, light wood with a curved back that rounds into armrests. Someone else’s tote bag sits in it, and it is missing one of his bright red cushions. I wonder if the back door still has the screen we installed so that air could flow through the space but not let Nuk escape, though I do not step outside to check.

Outside, the bench I built for Al to sit on among his small, potted garden has been taken by a neighboring unit. A small piece of silver wire is strung from a nail in the brick wall just outside the door, and I distantly recall Al explaining to me that he wanted a vined plant to grow along a wire and drape over the entrance to the bookshop.

It got close, as far as I can remember from faulty memory. The vine is gone, as is most of the wire, aside from this small piece, flashing in the sun.

–

On Saturday, October 23, 2021, I visited Al at the bookshop on a break from school. Several photos on my phone from that day are devoted to capturing Nuk lounging in pockets of sunshine in front of the history shelf — elegantly draping herself in front of authors like Brokaw, Bronner, and Brooks. According to a letter he wrote before I arrived, he made me a fresh pot of coffee and ate breakfast, hoping to impress me with his appetite, and we sat at a table toward the front of the bookshop, most often covered by a chess board, in two of his wooden chairs.

“Although tabletops are cluttered, the bookshop is clean I hope you’ll notice — and well-lit,” he wrote prior to my visit.

I don’t remember if I noticed, or if I vocalized it.

I hope I did.